Shades of Crip Time Within LIS Spaces .

“Shades of Crip Time Within LIS Spaces” examines the everyday experiences of crip time by Disabled, sick, and chronically ill people. Crip time is the name put to the experience of Disabled and sick people that "rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds" (Alison Kafer as cited in Ellen Samuels, "Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time," 2017). Crip time puts a name to the alteration and altering of time by Disabled people as a result of disability and illness; it might manifest as the extra time/planning needed to maneuver spaces, chronic pain and fatigue, and scheduling and rescheduling plans to accommodate yourself and/or others.

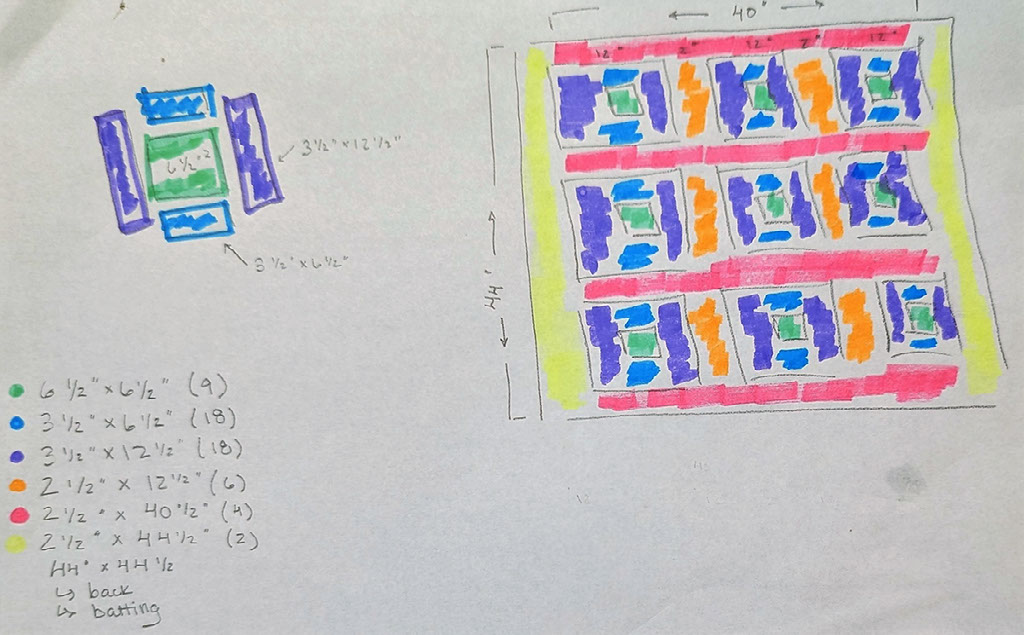

The physical representation of this project, a quilt, bridges the day-to-day of Disabled, sick, and chronically ill people (crip time) with the lives of observers in an academic setting (normative or non-crip time). The quilt features varying shades of beige and white in both the fabric, thread, and images to represent the (often) invisible labor that makes up crip time. This all being said, crip time is an academic term predominantly found within disability studies and it might not be an exact representation in the lives of Disabled, chronically ill, and sick people. The difficulty in translating crip time—the formal concept and/or general idea—is difficult to achieve in non-academic spaces, which is what drove this project. In general, Disabled people are often unable to experience LIS spaces in the ways that they were created due to inaccessibility and exclusion. This project demonstrates the varying degrees in which Disabled people experience ableism and inaccessibility within their own lives and by extension, LIS spaces.

------------

This project relies on the qualitative data gathered from a survey distributed to a myriad of school-related group chats as well as word of mouth. This survey introduced the topic of crip time—particularly, crip time within one’s own life. The survey asked for an image that demonstrates the participant’s representation(s) or interaction(s) with crip time as well as a caption or conceptualization of the meaning. To encourage critical thinking about crip time, I asked participants to consider four questions:

- How does crip time factor into your life?

- Was there a time in your life in which you did not utilize crip time? How has your life changed since then and now?

- In what ways do you find joy or liberation in crip time? What about grief?

- What are barriers do you have when experiencing crip time?

In total, I received four entries and included my own images and descriptions. This came out to eight photos which I translated into six images for the quilt.

The fabric I chose to use were old bed sheets that were either damaged or the wrong size. The choice of all beige was both circumstantial and intentional. It was what was available but it also demonstrated the invisible labor of crip time.

After cutting out all the pieces, most of my time was spent ironing, pining, and sewing everything together. This was largely the same for assembling the top piece as well as quilting all three layers together (quilt top, batting, and backing) which is seen here.

Adding the bias tape was the second to last step to finish the quilt. This was the first time I had used bias tape, so I had to look up tutorials on YouTube for help. The last step was to attach the images to the front of the quilt.

“Teaching critical disability studies as a methodology can be a way of shifting our students’ perspectives on the world…However, I emphasize to my students that my courses are not just about increasing student knowledge about disabled people, but also about changing the way students operate in their lives beyond the classroom, shifting the way they think, behave, and interpret the world around them. Incorporating a critical disability studies methodology into my teaching, therefore, means helping students understand (dis)ability as a social system that impacts all of us in a wide variety of systemic and quotidian ways…If my students are thinking critically about issues of (dis)ability outside of class, then I have provided them with not just knowledge or facts, but a critical perspective, an approach to interpreting the world.” (Schalk, 2017)

This quote from Sami Schalk (2017) highlights the main theme of my project which is that disability studies and disability justice are not solely academic perspectives and that they should be applied to everyday life. Crip time is an academic concept that has roots within the everyday experience of Disabled, chronically ill, and sick people.

Within LIS and in general, there is a divide between accessibility in theory and accessibility in practice, especially in regards to accessibility guidelines. Kumbier and Starkey (2016) found that the ALA (American Library Association) Core Values statement on Access and the Library Services for People with Disabilities policy “encourage what [Sara] Ahmed calls a “tick-box approach” (p. 106) to the problem of disability” where “what matters most is meeting specific, measurable goals and treating a given concern” (p. 477, as cited in Ahmed, 2012). Kumbier and Starkey expanded upon this point and emphasize that “[b]y focusing on solving individual users’ problems and positioning the library as able to provide services to users on its [the library’s] own terms…the literature does not attend to the larger structural, systemic, or social transformations that could enable access for all users; in other words this literature treats access as a matter of many minor adjustments and fixes rather than a sustained commitment to evaluating what access means for all users” (2016, p. 478). Eisenhauer Richardson and Carlisle Kletchka (2022) also add an significant point that “[w]hile these [accommodations] are important practices, they focus on what educators and museum staff can do for disabled visitors, rather than with them.” (p. 138-139, emphasis in original). In short, disability accessibility has not, does not, and will never be compatible with a “tick-box” approach; it must be a continued and ongoing conversation with disabled people and for disabled people.

In all, this project worked to highlight the discrepancies between the lived experience of disabled people, mostly disabled LIS graduate students, and the temporal realities that are expected of us. It is important to acknowledge that the accommodations and accessibility practices in place are often not enough, applicable, etc. for disabled students, and it is crucial to work with the disabled community around any given institution.

Recommendations

- Empathy building

- Participatory methods (aka community-driven) approach to accessibility

- Intersectionality

- Moving beyond the retrofit model of accessibility and the medical model of disability

References

- Brilmyer, G. (2022). “I’m also prepared to not find me. It's great when I do, but it doesn't hurt if I don't”: Crip time and anticipatory erasure for disabled archival users. Arch Sci, 22, 167–188. https://doi-org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.1007/s10502-021-09372-1

- Eisenhauer Richardson, J. T. and Carlisle Kletchka, D. (2022) Museum education for disability justice and liberatory access. Journal of Museum Education, 47(2), 138-149. 10.1080/10598650.2022.2072155

- Furlong, D. E. (2023). Enabling Crip Time With Digital Tools in Qualitative Inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 0(0). https://doi-org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.1177/10778004231163534

- Kumbier, A., and Starkey, J. (2016). Access is not problem solving: Disability justice and libraries. Library Trends, 64(3), 468-491. doi:10.1353/lib.2016.0004.

- Oud, J. (2019). Systemic workplace barriers for academic librarians with disabilities. College and Research Libraries, 80(2). https://crl.acrl.org/index.php/crl/article/view/16948/19429

- Samuels, E. (2017). Six ways of looking at crip time. Disability Studies Quarterly, 37(3).

- Schalk, S. (2017). Critical disability studies as methodology. Lateral: Journal of the Cultural Studies Association, 6(1).

- Sheppard, E. (2020). Performing normal but becoming crip: Living with chronic pain. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 22(1), 39-47. http://doi.org/10.16993/sjdr.619

- Williams, S. (n.d.). FREE Squared Quilt Pattern: The Perfect Beginner First Project. Suzy Quilts. https://suzyquilts.com/free-squared-quilt-pattern/

- Zorich, R. (2023). Everyday experiences with and within crip time. Google Forms Survey. https://forms.gle/mgS1TrHWLoTfsnqq9

River Zorich, MSLS Student at UNC-Chapel Hill, INLS 737 Spring 2023