Gray in the Rainbow LGBTQ+ Elders Care Needs and Death Literacy

In March 2020, when I was officially let go from work due to COVID-19, I finally decided to tackle a project I had been putting off for years: completing my end-of-life documents. For years I had a fear running through the back of my mind, should the worst happen and I suddenly die or be hospitalized and unable to speak for myself, my immediate family would be the ones who had control over my body, my burial rites, and my palliative care. As a queer, ex-Christian, I knew that they would not follow my wishes, but would instead hide my queerness and give me a Christian funeral, probably telling people I had returned to Christianity before death. The pandemic made death feel closer than ever, and I knew it was time to take control. It was a difficult process to write out what I wanted done after I died, if I was in a coma, what to do with digital accounts, what gifts people should bring, and all that paperwork. When I finished, I felt such relief. Not only was my biological family no longer going to dictate my final wishes, but also those I did want to put in charge would have everything they need, not have to worry about "what I would have wanted," because everything would be spelled out for them clearly and concisely.

For this project, I wanted to communicate my relationship with death and understand how other LGBTQ+ folks relate to it as well. Since coming out, I have been thinking deeply about what kind of elder I want to be, should I make it to old age. With such fraught relationship between my biological elders and myself, I yearn for closeness with LGBTQ+ elders, many of whom I have shared experiences with.

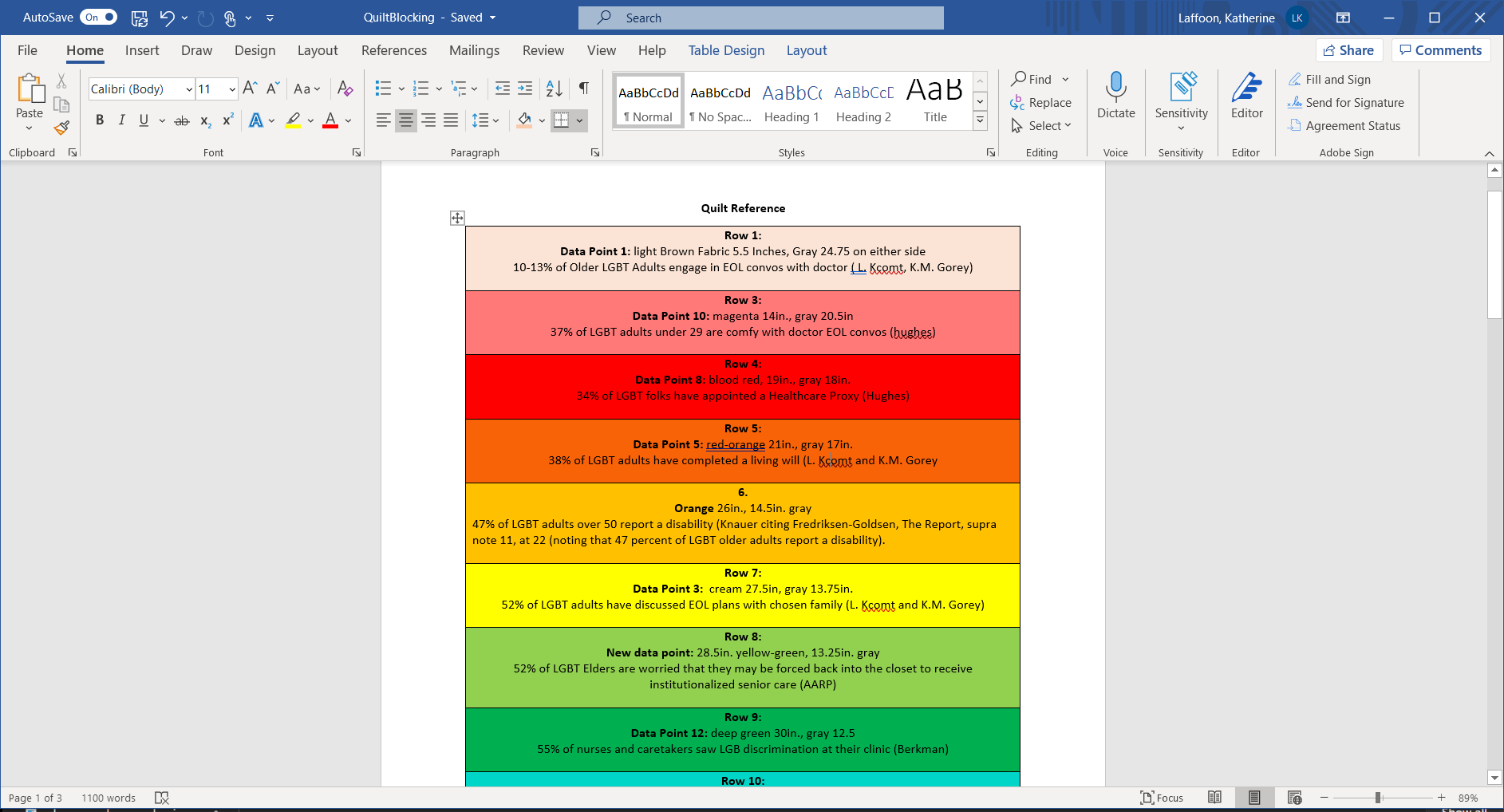

I took datasets relating to LGBTQ+ elders, their care needs, and their relationships with death literacy and wanted to create something that would feel warm and tender, rather than morbid and frightening. In conversation with my peers and in a kind of homage to the AIDS quilt memorial project, I translated the data into a quilt. This is the kind of quilt that you can snuggle under, and each bar represents a data point. I thought deeply about making a visually pleasing symmetrical design and about what colors to use. I shied away from using black to frame the rainbow colors, knowing its association with the macabre. I wanted to flip the stereotypes associated with that color and use it to represent the resiliency of the LBGTQ+ community, important as it is to me to include the brown and black stripes on our flag. The gray bordering each colorful bar instead speaks to me of liminal spaces, ambiguity, and transitions, all words that I find more appropriate when discussing death.

To no surprise, I found that LGBTQ+ people of all ages are much more likely to have completed wills than the general population. LGBTQ+ elders, very unlike the general population, largely want to die at home and are cared for by peers and chosen family. The large black stripe in the center represents the 90% of LGBTQ+ elders who are part of mutual care networks. These marks of LGBTQ+ resiliency are important to keep in mind when we look at the data about LGBTQ+ elders in institutional care. 55% of nurses have seen LGBTQ+ discrimination against elders at clinics and homes. 80% of those interviewed saw a friend, client, or were themselves intentionally misgendered by staff (the light purple stripes). 62% of elders say that they would worry about elder abuse should they or their partner suddenly need institutional care.

And, of course, something facing everyone is general confusion around what documents they need and when they are appropriate. One sobering study revealed that, while the participants had completed advance directives, living wills, and healthcare proxy documents only 25% could accurately say which document would take priority in a given situation. Healthcare providers answered with similar accuracy. This is a crisis of information. I believe that public librarians should be able to point to community resources around documents and accurate death care information, along with low-income options for thoughtful and meaningful death care. For those information professionals working in healthcare, it is critical that they understand the valid worries of LGBTQ+ elders when receiving care.

I hope that this project inspires death literacy. While a difficult topic, making meaning around end-of-life plans can be comforting and inspire tenderness, compassion, and motivation to live for what matters. I know that I am now considering daily what is worth my time and how I can live to grow into a good elder for my community.

Sources:

Abel, J., Bowra, J., Walter, T., & Howarth, G. (2011). Compassionate community networks: Supporting home dying. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 1(2), 129. doi:http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.1136/bmjspcare-2011-000068

de Vries, Brian and Gloria Gutman. 2016. "End-of-Life Preparations among LGBT Older Adults." Generations 40 (2): 46-48. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/scholarly-journals/end-life-preparations-among-lgbt-older-adults/docview/1812643835/se-2?accountid=14244.

Doughty, Caitlin [Ask a Mortician]. (2020, March 14). Protecting Trans Bodies in Death [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PVgumSUZQRI&t=169s&ab_channel=CaitlinDoughty%E2%80%93AskAMortician

Horsfall, D., Noonan, K., & Leonard, R. (2012). Bringing our dying home: How caring for someone at end of life builds social capital and develops compassionate communities. Health Sociology Review, 21(4), 373-382. doi:http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.5172/hesr.2012.21.4.373

Houghton, Angela. Maintaining Dignity: Understanding and Responding to the Challenges Facing Older LGBT Americans. Washington, DC: AARP Research, March 2018. https://doi.org/10.26419/res.00217.001

Karen I. Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., The Aging and Health Report: Disparities and Resilience among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Older Adults (2012), http://depts.washington.edu/agepride/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Full-report10-25-12.pdf

Kcomt, Luisa and Gorey, Kevin M. (2017). “End-of-Life Preparations among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Integrative Review of Prevalent Behaviors.” Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 13 (4), 284-301. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/socialworkpub/57

Knauer, Nancy J. “LGBT OLDER ADULTS, CHOSEN FAMILY, AND CAREGIVING.” Journal of Law and Religion 31, no. 2 (2016): 150–68. doi:10.1017/jlr.2016.23.

Marietta Radomska , Tara Mehrabi & Nina Lykke (2020) “Queer Death Studies: Death, Dying and Mourning from a Queerfeminist Perspective,” Australian Feminist Studies, 35:104, 81-100, DOI: 10.1080/08164649.2020.1811952

Noonan, K., Horsfall, D., Leonard, R., & Rosenberg, J. (2016). Developing death literacy. Progress in Palliative Care, 24(1), 31–35. https://doiorg.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.1080/09699260.2015.1103498

Wilson, K., Kortes-Miller, K., & Stinchcombe, A. (2018). “Staying Out of the Closet: LGBT Older Adults’ Hopes and Fears in Considering End-of-Life.” Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue canadienne du vieillissement 37(1), 22-31. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/692587.

Witten, Taryyn M. “It’s Not All Darkness: Robustness, Resilience, and Successful Transgender Aging.” LGBT Health Mar 2014.24-33.http://doi.org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.1089/lgbt.2013.0017

Witten, T. M. (2016). The intersectional challenges of aging and of being a gender non-conforming adult. Generations, 40(2), 63-70. Retrieved from http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/scholarly-journals/intersectional-challenges-aging-being-gender-non/docview/1812643027/se-2?accountid=14244

Special Thanks to the staff at Cary Quilting Company for helping me choose backing fabric and to Dr. Casey Rawson who took time to let me talk through this my very first quilt project.

Credits:

Photos taken by me.