“We are the most important resource” Care Gaps and Community Responses - Transgender and Gender Variant Healthcare in the South

Data shows that transgender and gender variant people in the south, especially Black trans and gender variant individuals, face far worse issues with physical health, mental health, and access to healthcare than cisgender people, illustrating serious gaps and problems within the medical system. This includes worse physical and mental health, higher rates of abuse and violence and suicidal ideation, less quality care and higher rates of medical mistreatment, increased likelihood of being under- or uninsured, and increased likelihood of not feeling comfortable seeking care (Harless et al., 2019)*. Additional gaps and problems include lack of resources, lack of informed providers, lack of access to care, and outright discrimination. At the same time, transgender individuals rely on each other to fill these gaps. This data physicalization project explores the number of “official” resources that exist for trans people in the south and the important and complex reality of community, peer-to-peer, financial crowdfunding, and online support.

*I will not be listing specific data on these numbers. If you want more information, see the Campaign for Southern Equality's 2019 Southern LGBTQ Health Survey and the Breakout Report on Black Transgender Southerners, and the various reports from the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey.

Taking the form of a wind chime, the artifact visualizes the barriers to healthcare, the "official" resources in each state, and the gaps in between. The sounds the wind chime makes as the physical gaps are filled when the objects connect represents community and peer support.

The Base: The Barriers

Data Set 1: 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey

- 33% of trans people do not seek care due to cost

- 23% do not seek care due to fear of mistreatment

- 33% of those who do seek treatment have a negative experience related to their gender identity

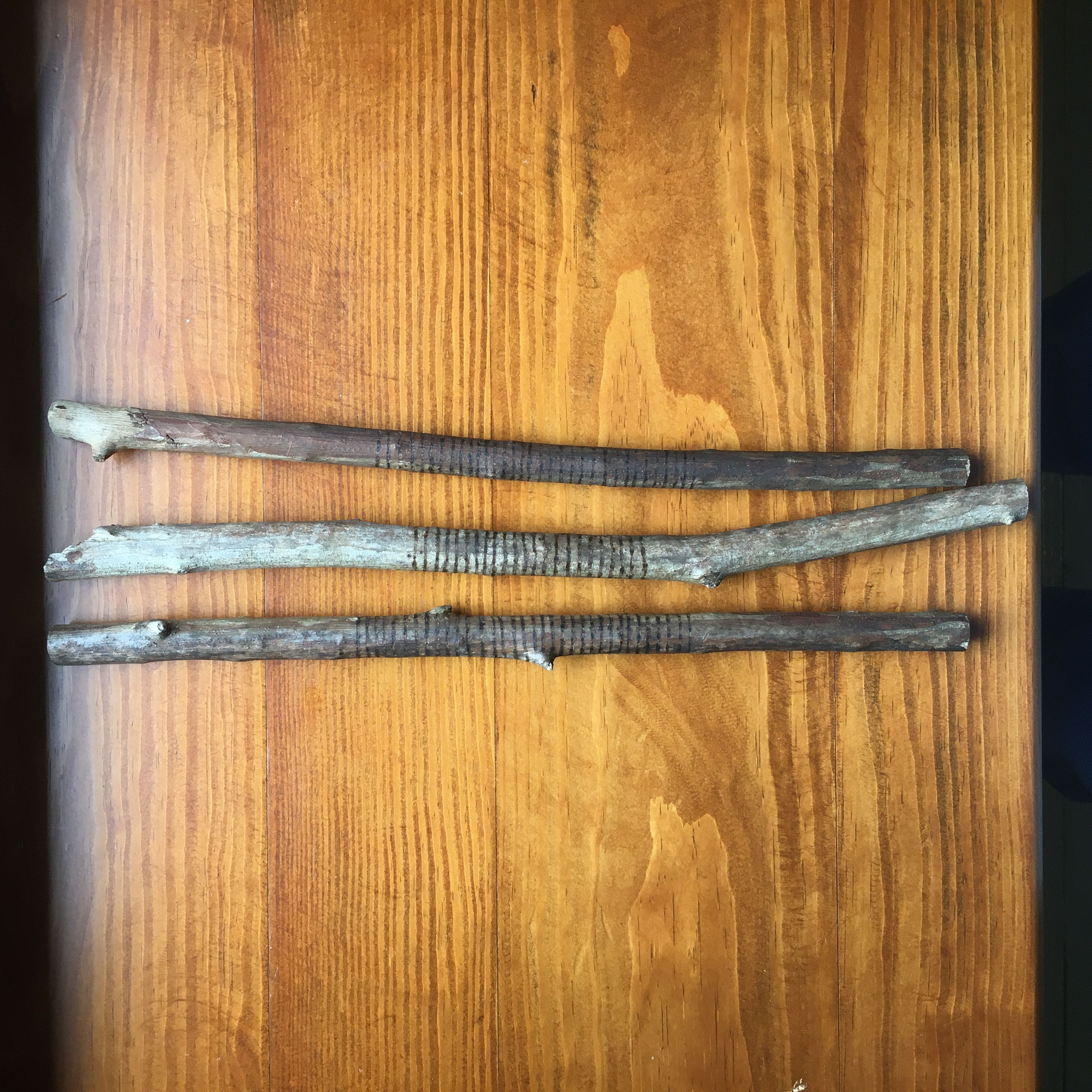

These percentages are wood-burned into the base of the wind chime, represented by rings around the wood.

I wood-burned rings around these found sticks, each stick representing a statistic listed above.

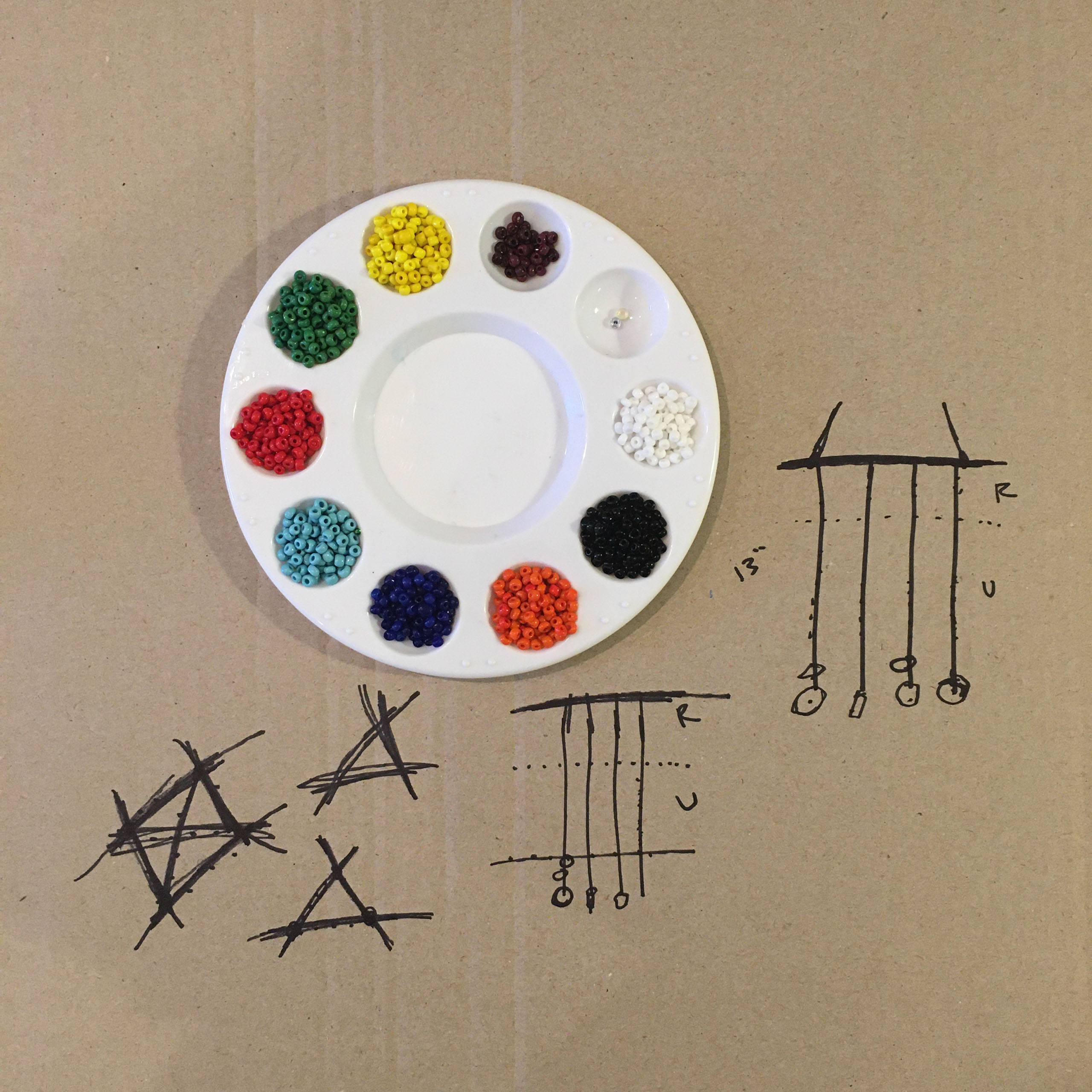

Next, I drew out a basic plan of the base of the wind chime, planning each string about an inch apart along the base. Figuring out the angles of the cuts was kind of difficult since the sticks were irregular in shape so it was a combination of measuring and guesswork. After sawing the sticks, I drilled through where the sticks met, placing a nail with super glue through each hole (pictured here). I then sawed off the end of the nails so it was flush. It was actually nice that the sticks did not perfectly meet together because I was able to wrap wire around the nail between each stick to use as anchor points to connect the chain for the top of the wind chime.

The What: The "Official" Resources

Data Set 2: Trans in the South Guide

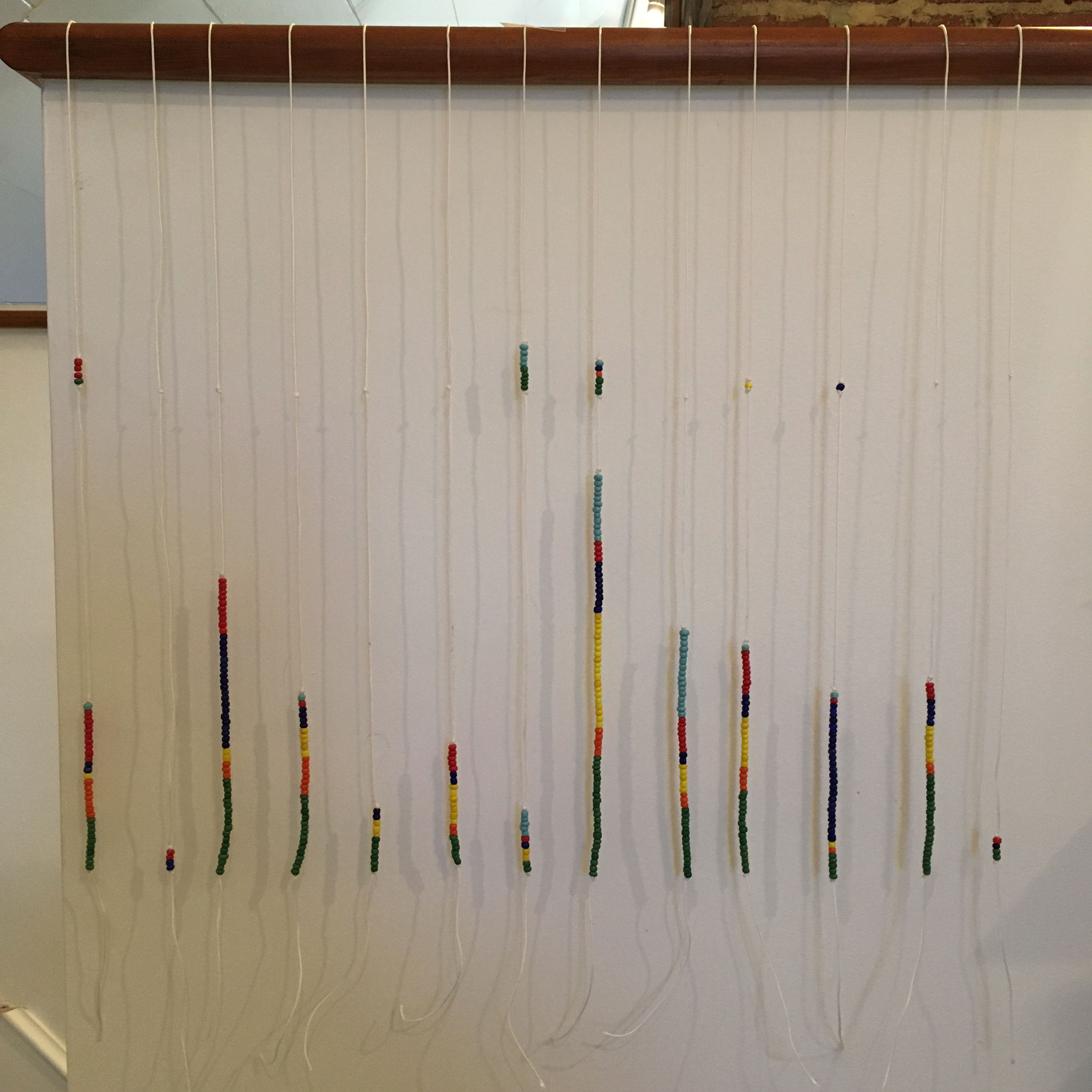

This guide from the Campaign for Southern Equality (CSE) lists different resources and services for transgender and gender variant individuals broken down by state and category. Each strand of the wind chime represents a state: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, West Virginia (shown in order left to right on the image). Each bead represents a different resource in the state.

- Green: mental health providers

- Orange: endocrinologists

- Yellow: primary care

- Dark blue: Planned Parenthood

- Red: HIV care

- Light blue: legal services

Urban and Rural Differences: I used a list of rural counties to delineate if the service is located in an urban or rural county. The resources in an urban county are at the bottom of the string, while the resources in a rural county are towards the top. Many states do not have any resources in rural counties, represented by a single knot in the string.

A note on data limitations: CSE is located in North Carolina, potentially impacting the number of resources found in and around NC compared to other states in the south.

The Gaps and Connections

Data Set 3: 2018 Southern Trans Health Focus Group Project, personal stories and experiences

While there are a lack of official resources, especially in rural areas, trans and gender variant individuals fill these gaps with each other through sharing information and resources, organizing support groups, and connecting online.

These connections are vital. They are also difficult to measure since they might be shared in casual conversations, passed through zines or word of mouth, protected, or purposefully kept secret. These connections, these communications, these sounds are both very real and embodied and also somewhat intangible and difficult to predict.

"If we don’t talk to each other and let each other know who is doing what, who is doing it appropriately, and who is doing it inappropriately, we won’t know. If you’re trans [...], you’re an important resource for us and we are an important resource for you [...] We are the most important resource.”

- from The Report of the 2018 Southern Trans Health Focus Group Project

In many ways this project was years in the making. Since I was a teenager, I have a habit of picking up discarded things, beautiful things on the ground.

I attached each object, representing trans individuals in each state, by tying knots and using hot glue. I considered matching each state with a certain object that spoke to some sort of symbolism, but ended up choosing random objects. My main criteria for the order were the sounds that each object made when colliding with the adjacent object.

Action: Fight for universal, comprehensive, accessible, trans-affirming healthcare.

Also...

1. Doctors, medical practitioners, mental health providers, and anyone involved in the health and healthcare system need better education on providing trans-affirming care as well as the intersectional needs of different communities. Medical school curricula in the United States and Canada spend a median of five hours on LGBT content in general, while nurses in the United States spend a median of two hours on LGBT content (Luctkar-Flude et al., 2020). However, the reality is not all providers are going to take responsibility to do additional professional development so it is also important that we also work to expand access to already existing trans-affirming healthcare through telehealth, access to transportation, and lowering costs.

2. Facilitate more community and peer connections. This could mean more formal connections through in-person or online support groups or facilitated online resources sharing. However, with formalization there are always risks surveillance and hypervisibility to take into account. More "informal" and private/secure connections are also important and valid. This means also focusing on digital inclusion through expanding access to broadband and affordable devices so people can communicate.

3. Fight against harmful and discriminatory policies at all levels. As of April 2021, twenty-one states are attempting to pass discriminatory legislation mostly in the form of banning transgender youth from sports and making it illegal to provide trans-affirming care to trans youth. Legislators are attempting to codify discrimination, define and police transgender bodies, and deny life-saving care. Learn more by visiting the National Center for Transgender Equality's State Action Center.

Overall, these inequities that trans and gender variant people face are not just healthcare issues, but also issues of racial, income, geographic, information, and digital inequities. Therefore the actions and solutions must be focused on intersectional justice.

Thank you to Dr. Melo and all my peers for their support! And a big thank you to my team in all things involving engineering and power tools: my parents.

References

Gibson-Hill, I., Beach-Ferrara, J., White, C., & Scott, A. (2019). Trans in the South: A Guide to Resources and Services, Campaign for Southern Equality.

Harless, C., Nanney, M., Johnson, A., Polaski, A., & Beach-Ferrara, J. (2019). The Report of the 2019 Southern LGBTQ Healthy Survey, Campaign for Southern Equality.

Johnson, A., Gibson-Hill, I., & Beach-Ferrara, J. (2018). The Report of the 2018 Southern Trans Health Focus Group Project, Campaign for Southern Equality.

Luctkar-Flude, M., Tyerman, J., Ziegler, E., Carroll, B., Shortall, C., Chumbley, L., & Tregunno, D. (2020). Developing a Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Nursing Education Toolkit. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 51(9), 412–419. http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.3928/00220124-20200812-06

Rivera, I., Flores, A., Merson, D., & Rauch, M. (2016). Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality.

Stasio, F. (Host). (2019, February 27). How Can Transgender Southerners Get Better Healthcare? [Audio podcast episode]. In The State of Things. WUNC. https://www.wunc.org/show/the-state-of-things/2019-02-27/how-can-transgender-southerners-get-better-healthcare

United States Health Resources & Services Administration. (2018). List of Rural Counties And Designated Eligible Census Tracts in Metropolitan Counties.