Bibliotarot Ashley Werlinich: INLS 690

Inspiration for the project

This Bibliotarot is inspired by my love of early modern print media, my practice as a tarot reader, and my love of surreal and iconographic imagery. For this project, I remixed 16th and 17th century woodcuts found both in my work at Wilson Library and in my studies as an early modern scholar--blending them with traditional tarot imagery, surreal detailing, and images of personal importance to me. By collaging, embellishing, and remixing woodcuts via digital design software, this tarot deck juxtaposes the early modern tradition of woodcut reuse in cheap print with the repetition of iconographic imagery in sacred and occult texts.

In much the same way that 3D models and laser cut templates are remixed in makerspaces today, in 17th century Europe woodcuts were re-used and remixed as a common practice. As the English Broadside Ballad Archive reminds us, woodcuts were used (and re-used) both in cheap print and across more "legitimate" print media. As woodcuts were repurposed, re-used, or referenced in other ballads or works, they brought with them existing layers of meaning, while also forming new meaning. And tarot, too, reflects this process; its iconography is referential to that which has come before it, but the meaning of the iconography is both informed by cultural understanding of symbols as well as personal interpretation of the images.

To find out more about woodcut reuse, read Early Modern Memes: The Reuse and Recycling of Woodcuts in 17th-Century English Popular Print (Katie Sisneros, The Public Domain Review)

In the spirit of early modern woodcut re-use, I used digital design software (Procreate) to combine and re-imagine images. This particular software allowed me the freedom of mixing images drawn from other texts with those from my own imagination, while still unifying the images into one streamlined final product. For an example of how I went about remixing images, watch the drafting video for "The Emperor" below:

In addition to remixing woodcuts from early modern books, I also overlaid the designs on images of pages from a vintage astronomy textbook (The New Golden Book of Astronomy), selecting pages that resonated with the meanings of the particular cards to use as a background. I chose to use this book because it is a book that I often use in my cut paper art, so it holds a great deal of personal meaning to me. I also felt that mixing early modern woodcuts with a midcentury book accentuated the deck's anachronism, while emphasizing the thematic ties tarot has to planets and the universe.

In addition to the collage work I did for the front of the cards, I also used Layout (a photo collage app for Instagram) to create a pattern for the card backs from a photograph I had taken of a reader's annotations on a Wilson Special Collections Library copy of Historia plantarum (a 16th century Herbal). I chose to highlight this particular image for the card backs, as I thought that it displayed a meaningful interaction between reader and object, something that is so important both when reading books or reading tarot.

tarot as "book"

But how, then to get from merely using components of books as the backbone of the art to thinking of the tarot deck as a re-imagining or "hacking" of a book?

Tarot is, in a sense, a type of "book." Tarot cards (like books) are points of personal reflection; both books and tarot can help you work through emotions, gain empathy, and understand other paths and possibilities. Reading tarot (like reading a book) is also open to interpretation; while tarot cards do have traditional meanings associated with them, how a particular person absorbs their meaning is quite open to their own experience of the cards. Unlike a book, however, tarot is meant to be moved around--it is meant to be experienced in a nonlinear fashion. As tarot changes with the relative positions of the cards in a spread, my question as I began this project became focused on how to make something that both acts like a "book" of sorts and also as a functional tarot deck.

In order to create a tarot deck that was both moveable yet still a "book," I turned to another source of inspiration from my work at Wilson Special Collections Library--palm leaf manuscripts. Palm leaf manuscripts (which were used in South and South East Asia as early as the 5th century CE) consist of long palm leaves bound between two endboards. Unlike most western bindings, this binding style allows the reader to disbind the book by taking out the cord that holds the boards to the leaves. As such, it was a perfect choice for a binding for my tarot cards.

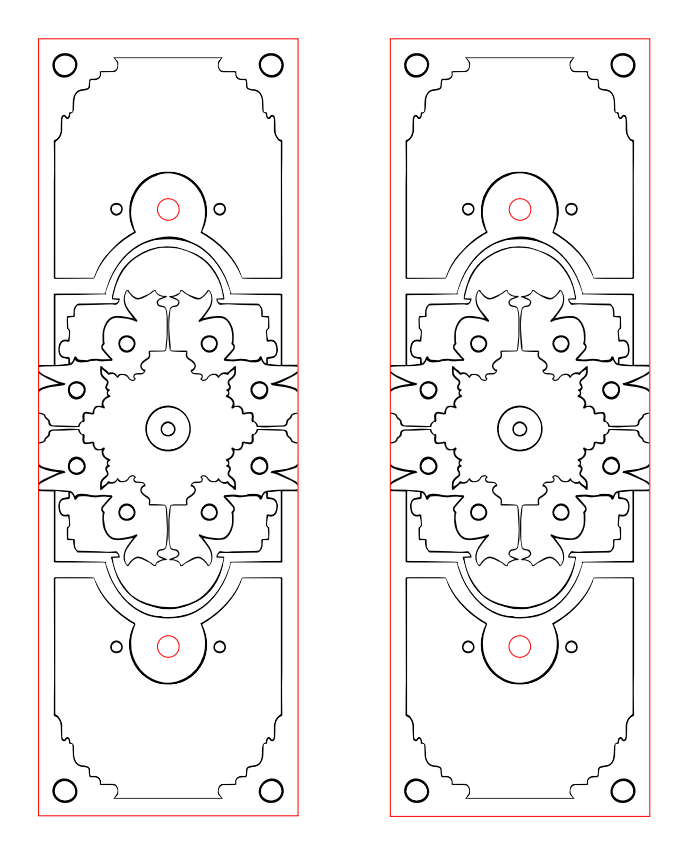

In order to mimic a palm leaf manuscript format, I created elongated cards and bound them between laser cut endboards. As olas sometimes have elaborately patterned endboards (as seen above), I decided to rework a pattern I found on an early modern breviary for my endboard design. I did this both pay homage to the original format, as well as to allude to the bindings of the era and region of the woodcuts I remixed.

augmented reality & layers of interpretation

In addition to the physical elements of the tarot, I wanted to incorporate a digital interface to provide readers with an interpretive element. As readers might not have familiarity with tarot, I thought it would be helpful to use augmented reality to unlock this extra layer of meaning.

While the cards themselves only include the image and their corresponding number, I used the augmented art app Eyejack to uncover an additional layer of text; this layer includes the card name, as well as keywords associated with interpreting the cards. The keywords were taken from Labyrinthos, an interpretive website I used to teach myself tarot reading when I first began.

Setbacks and reflections

Overall, the making process was really enjoyable--however there were a few snags that I hit during the design and iterating process. Initially, I had considered building in an AR component for the card selection process in addition to the interpretive AR on Eyejack, as I thought it could be an interesting way to present the deck virtually if users could not interact with the deck. However, the process of building this tool on Metaverse didn't provide me with the functionality or interface I wanted, so I decided to ground the deck solely in the physical object (with an augmented interpretive element), rather than also providing a digital alternative to the deck itself. While Metaverse was not the best tool for this particular project, using Eyejack for AR elements was very customizable and user friendly, and worked well for my needs. The app's purpose as a multimodal art tool allowed me to work within the dimensions I wanted to, and also allowed me to use the actual art to trigger an interactive element, rather than having to have the digital component be separate from the book itself.

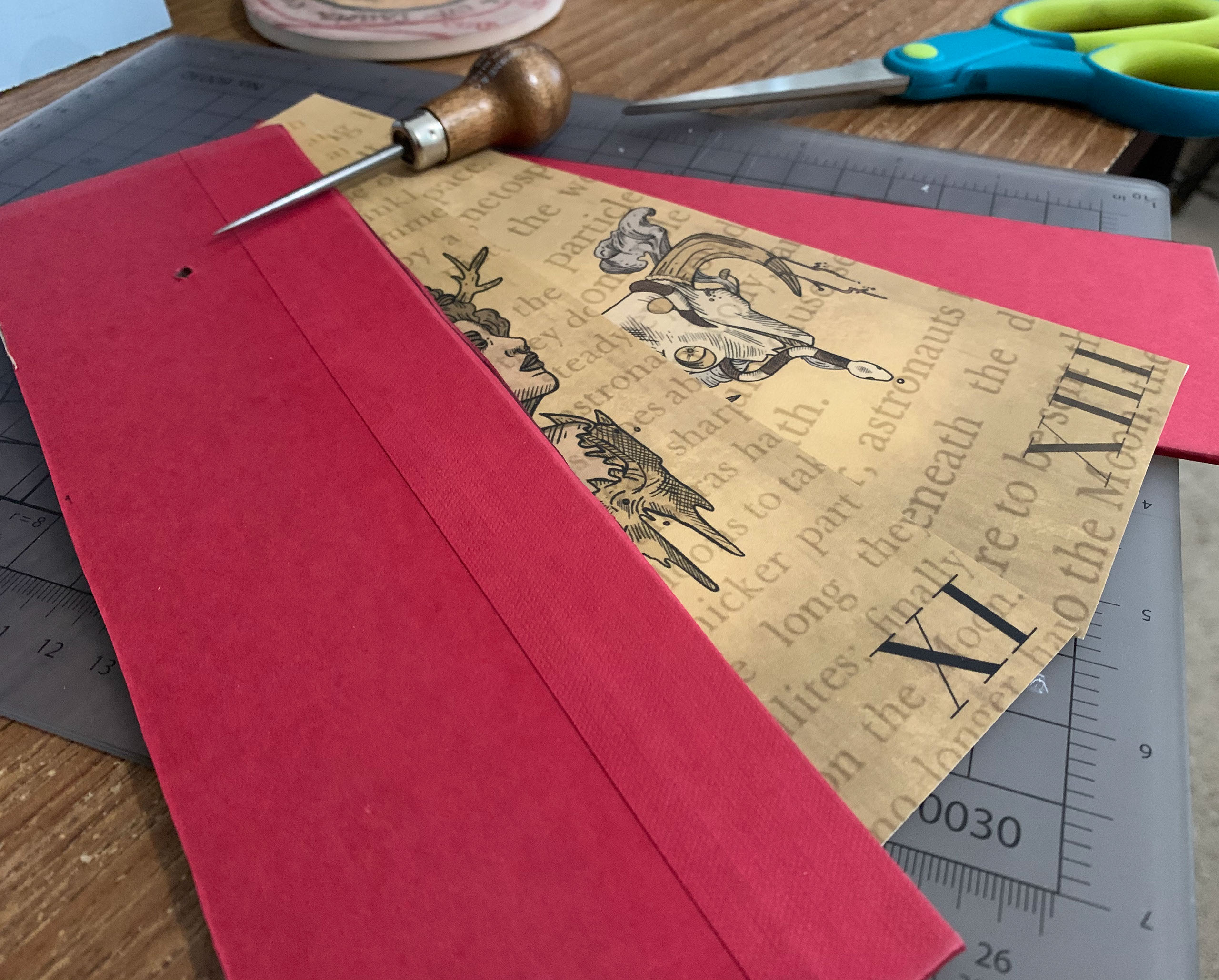

Additionally, I went through several prototypes of the endboards in the iterative process in order to envision how they would work and how they should look with the cards. In order to see how they worked, I first made them out of endboards from an existing book, and punched holes with an awl.

However, as I iterated with repurposed materials, I decided that laser cutting would be the ideal mode of composition. It still took a few attempts with the laser cutting to see what I wanted, as I wasn't sure if I wanted the endboards to be incredibly ornate and decorated or more minimalist. While the first endboards I made were simple wooden boards that I decorated with craft foam and painted, I decided that the look and feel of the plywood (with designs cut into it rather than built onto it) provided me with the look I wanted from the deck.

Overall, this project was a really useful reminder that making in new mediums always has its frustrations and often requires multiple drafts even for things that are seemingly straightforward; as such, it was a good demonstration of why we should always be transparent about the frustrations and multiple iterations we need to do in our own work, so that makerspace users feel supported and comfortable while encountering frustrations and setbacks.

WORKS CITED

"A Godly Guide of Directions / for true penitent Sinners in these troubled times. / That we call to God to be our friend, / To think upon our latter end, / Mans Life is short and at no stay / Wee almost have a dying day, / That God may guide us along, / To bring us to our heavenly home, / Where our Souls may live and ever rest / With heavenly Angels that are blest." (Printed for P. Brooksby at the Golden Ball in Pye-corner, 1672-1696). English Broadside Ballad Archive. Accessed 3 November, 2020. https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/30660/album

"Death's Uncontrollable Summons; / OR, The Mortality of MANKIND. / Being a Dialogue between DEATH and a YOUNG-MAN." (Printed for P. Brooksby at the golden ball in Pye-Corner, 1685). English Broadside Ballad Archive. Accessed 3 November, 2020. https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/30571/album

Image of Nineteenth century Kammavāca palm leaf manuscript from Laos written in Tham Script. (2015, February 24). Lao collection at the British Library now fully catalogued. Asian and African Studies Blog; British Library. https://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/asian-and-african/2015/02/lao-collection-at-the-british-library-now-fully-catalogued.html

Sisneros, K. (2018). Early Modern Memes The Reuse and Recycling of Woodcuts in 17th-Century English Popular Print. The Public Domain Review. https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/early-modern-memes-the-reuse-and-recycling-of-woodcuts-in-17th-century-english-popular-print